Look more closely at just about anything, and the more closely you look, the more you see. The world is incredibly complex, and you don’t notice that until you really look.

But sometimes things at first glance are so brutally simple you don’t see them at all.

And then there’s this moment, this flash of lightning, and all of a sudden – ka-ching! – and then you see it, and everything suddenly looks different, in a new light.

Say you’re walking on a street, could be anywhere in the USA, like this scene on a street corner in a small town in the middle of nowhere:

Nowhere, in this case, being Morton, Mississippi, and that’s the Morton Bank you’re looking at, and this is the photo I found on Google Maps, taken only a few years ago.

But take a ride on a Time Machine, all the way back to 1971, and now it’s an evening in early fall and everything in town is all closed up. And you don’t live in Morton, you’re a stranger, just passing through on your way home, back to Memphis.

And you stop the car. And get out. And look across the street. And raise your camera and look through the viewfinder. Click. And now it looks like this:

There it is again, in the greenish glare of the mercury street lamp. The Bank of Morton, the letters chiseled on the facade above the awning.

Back then, when it was built in the late Twenties in the Art Deco style, with its massive volume and ornate geometrical design, it was an emblem of the future, a bright promise of luxury and glamour and Progress.

A dinosaur spawned with countless others just before the meteor of the Great Depression struck. Now here it is again, more than 40 years later, a forlorn vestige, a ghost ship adrift in the vastness of space/time, a deserted street, a half-moon and a street-lamp sun set in a stunning purple glow. Planet Earth. Ka-ching.

But today, it just looks like the first scene in this post. It could be any street, anywhere in the USA.

The man from Memphis, who took the photo, is William Eggleston, aka Egg to his friends, and as of today, he’s still here on Planet Earth. But now, many people think he’s the best photographer in America. And that he revolutionized the medium, and brought color into photography in a way no one had ever done before.

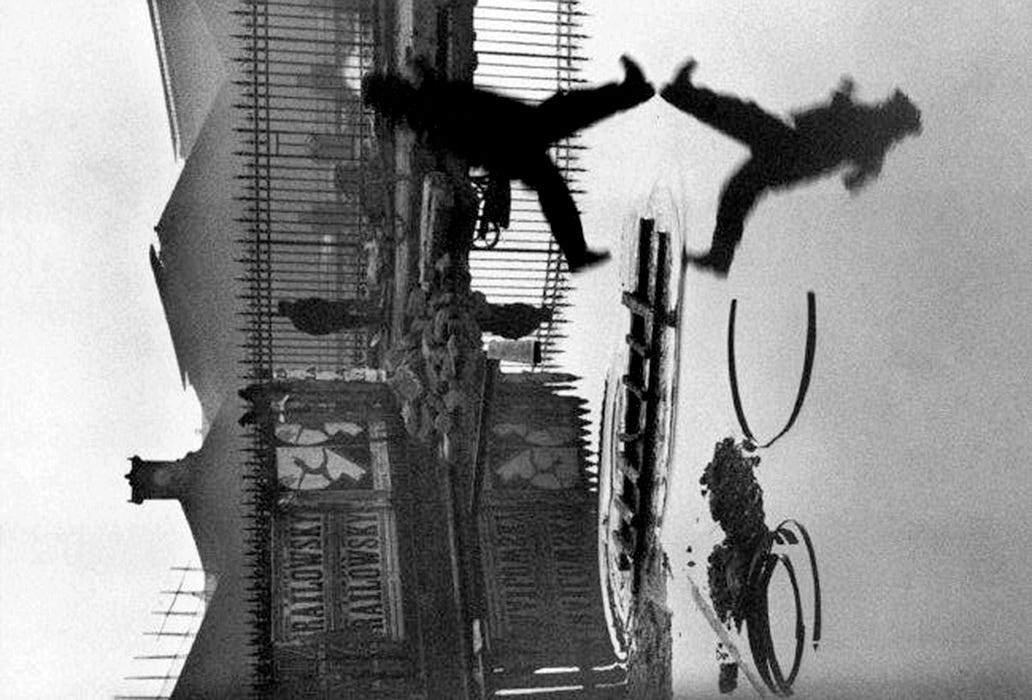

But I have a confession to make. When I first saw some of Egg’s work, back in 1976, at a one-man show at MoMA, I didn’t get it at all. Like a lot of people, I was upset. What we saw was an egregious violation of our Idea of the Art. Meaning rigorous black-and-white photography, the kind MoMA’s permanent collection is chock-full of. Walker Evans, Paul Strand, Steichen and especially the guy at the very top of the pyramid. Henri Cartier-Bresson.

And those exquisite and elegant Decisive Moments. Everything in magical order within the frozen frame.

In Egg’s photos, there are no such moments. Only a celebration of Banality. And a lot of vulgar Color. Ugh.

And another confession. When Robert Frank’s The Americans first came out in 1959, there were any number of people who looked at them and saw only grainy b/w photos, some tilted at an angle, others out of focus. Photos of people you couldn’t even see, hidden (or hiding) behind masks and flags. Dark seedy motel rooms, people stuck in elevators, or staring back at the camera from a bus. What was that all about?

I was among them. Another idiot seeing something so brutally simple that I didn’t see anything at all. But within ten years, people were not only seeing what was there, there were legions of photographers roaming the streets and highways of America, trying to find their own Robert Frank photos.

And when that happened, was Robert Frank thrilled by all that recognition? No. He moved from New York to a tiny, desolate village on the western edge of Cape Breton Island, in Nova Scotia. And wrote a postcard to a friend. All it said was, “I’m famous. Now what?” And he never took another photo again that looked like a Robert Frank.

And now Frank is gone, but like the Sondheim song about the formerly famous has it, Egg is still clocking in at 86 as I write this.

I suppose it’s one of the ways you can tell great art. And maybe if your first impulse isn’t one of rejection, then perhaps it isn’t great. It takes a while, and you have to really look, closely. But when enough people do, a critical mass builds, and the moment arrives at last, and what you see is no longer just a collection of pixels, but a new kind of art.

Ever since then, legions of Egg impersonators have tried to do what he did. But Egg doesn’t have to worry. He can stay right where he is. Egg doesn’t know how he does it either. He just does it. And never, so he says, takes more than one of each. Click! And either he gets it, or he doesn’t. All or nothing. Now or never.

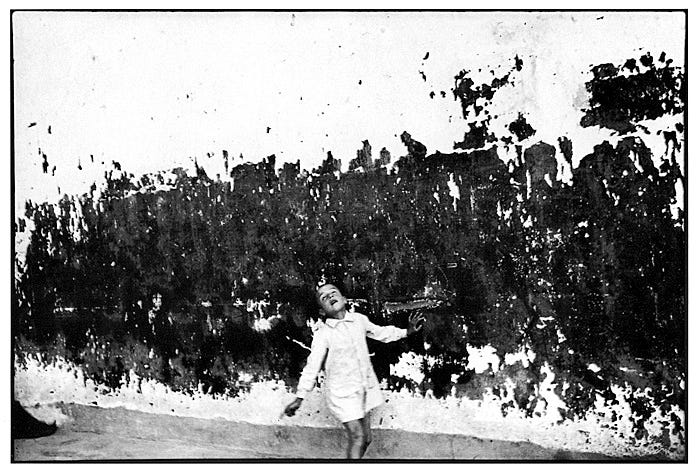

I leave you with one more set of pixels, one more Egg. Probably taken on the same trip through Morton. This one on the outskirts of town. The same lurid green of the mercury lamp shining on the dirt road behind. The same purple glow in the sky above. It’s Halloween. And as true a picture of the Human Condition as I’ve ever seen. A decisive moment? No. But it’s an image I can’t forget. An image I can barely look at.

Leave a comment