So here I am, reading The NY Times. About the baffled reaction of NASA scientists to the new photos of the surface of Pluto. Ice Mountains! No craters! Strange cracks on the surface. And then this NASA guy says “we’ll all have to put on our thinking caps.”

And I begin to wonder about where that phrase – thinking cap – comes from. It seems the term is fairly recent, going back only about 150 years or so. Before then, people called it a “considering cap.”

Here, for example, is Robert Armin, writing in a 1600 pamphlet, “Foole upon foole”: “The Cobbler puts off his considering cap, why sir, sayes he, I sent them home but now.”

So it seems a considering cap is a sort of mental metaphor for cobbling your thoughts together. And even more interesting is the notion that once you take this cap off, your thoughts are sent home! Where they came from. As though they live in some space under the cap, lying asleep, waiting to be summoned forth the next day into further consideration.

So here, 300 years before Freud, we have a curious, primitive forerunner of the idea of a conscious mind (the cap, a crude image of the neocortex) sitting atop an Unconscious Mind, a place where thoughts originate, at home within us, but at rest, as it were.

There’s no evidence I can find that the metaphor was taken literally, and that people actually wore such caps as an aid in helping to bring their thoughts to conscious awareness and assembling them into coherent ideas. But there is a drawing of one!

From The History of Little Goody Two-Shoes, a children’s story, a variation on Cinderella, published in London in 1765. With this description:

“…a considering Cap, almost as large as a Grenadier’s, but of three equal Sides;

on the first of which was written, I MAY BE WRONG;

on the second, IT IS FIFTY TO ONE BUT YOU ARE ;

and on the third, I’LL CONSIDER OF IT.”

So considering involves weighing the possibility that you *might* just be wrong, versus the overwhelming probability that you are right! The basic duel between opposites, disproportionately biased in your favor. However, room is left for a third option: to reflect further on the matter. And indeed, the word “consider” (from the same root for “sidereal”) originally meant to reflect upward, on the heavens, and let your thoughts be with the stars.

So here we have another kind of cap, that sits above us – a starry world upon which we may project our unconscious thoughts, in somewhat the same manner as ancient civilizations saw archetypal patterns in the stars and named them as constellations, like the Bull or the Scorpion. Consider long enough, and a pattern will make an appearance on the sky of your mind, your considering cap.

But let’s consider this further. And return to Robert Armin, the fellow who wrote that pamphlet about fools back in 1600. Any idea who he was? I didn’t have a clue. But surprise – it turns out that Armin played a very significant role, quite literally, in our theatrical history. The actor who first performed The Fool in Shakespeare’s King Lear at the Globe Theatre, when it opened on December 26, 1606!

Mr. Armin was no ordinary fool. It seems he invented the very Idea of the Fool. Or created an entirely new way of performing that character. And maybe a new kind of Performance Art.

Lower-case “fools” have always been around. Air-heads, from the Latin root for bellows. But sometime in the middle of the Middle Ages (ca. 1275), the meaning shifted to “madman” – as in fou, French for crazy – someone acting outside the strict norms of Christian society that constitute proper, rational behavior. And soon after that, it became a job, a specialty act, the job description requiring foolishness enacted on purpose.

A Fool or jester (Armin calls him an “artificial” fool) became just a hired hand, a lackey, a deliberately impious rascal, employed in a royal or noble household to provide wit and entertainment, and to flatter his master.

A good fool was a skilled performer, an artisan who displayed his finely-honed wares in public. Indeed, the best fools often gave solo shows, a kind of spontaneous battle of wits between the Fool and members of the audience, to see who could make a better fool of the other.

These were jovial social events, in which the community gathered to share a good laugh, jesting and jousting with one another. But Armin’s Foole (he calls him the “natural fool”) offered a whole new take on the matter. Madness became a method. A primitive talking cure. (And by the way, one of the first theaters where Armin performed his new tricks was right next door to Bethlem Hospital, aka Bedlam, the asylum for the insane.)

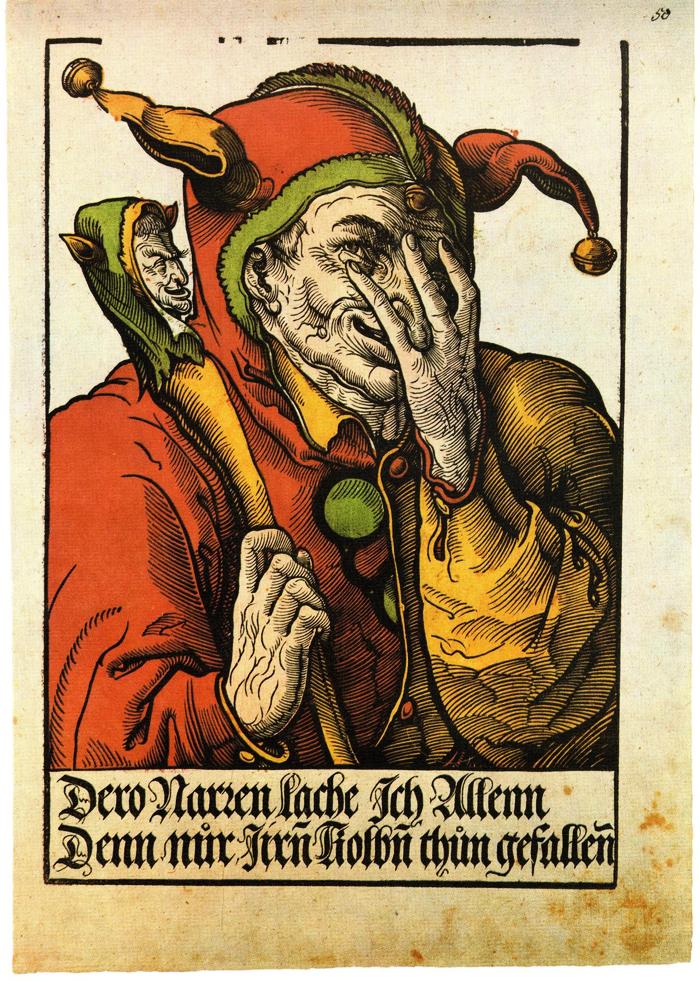

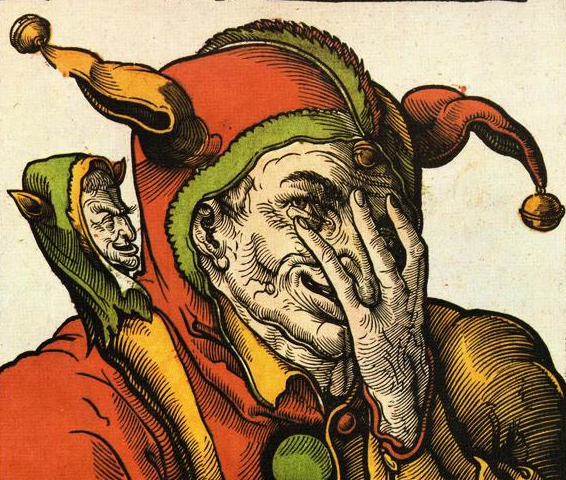

A painting of a fool, with his marotte — a prop stick, imitating a scepter, an emblem of the king of wit. And carved into the top of it is a miniature portrait of himself. The fool would use his marotte to make comic gestures, rap on the ground to call for attention, point to people and deliver crushing blows of wit upon his opponents. So besides being a parody of royal power, it was also a kind of cudgel.

But here is where Armin went a step further. He personified his marotte, and named it Sir Truncheon. And talked to it as if it were a real person. And it talked back. Not to the audience, but to Armin himself.

It became a kind of running dialogue between the two sides of the fool – hence the title of Armin‘s pamphlet: “foole upon foole” – one side pretending to be wise and noble and good, and the other, natural side, who makes fun of the other’s pretensions and foibles. This natural fool no longer flatters and entertains his master. This fool is mad to tell the brutal truth. He no longer swears allegiance to his master, but to Nature. And the audience no longer participates, it watches the unruly drama unfold, between a mind divided against itself.

And there you have King Lear — a noble fool if ever there was — disowned by his own daughters and stripped of his power, he cannot face the brutal truth of his situation, above all, that he has brought it upon himself though his own willful blindness. What is happening to Lear is… unthinkable.

As the Fool tells him: “I had rather be any kind o’ thing than a fool. And yet I would not be thee, nuncle. Thou hast pared thy wit o’ both sides and left nothing i’ th’ middle.”

Lear cannot put on his 3-sided thinking cap. He’s lost his wits and cannot tell right from wrong, nor consider anything in between. Three sides, three daughters. Two wicked daughters take him for a fool and divide his kingdom, while the third refuses to flatter her father, and is rejected for her honesty. So it is left to this Natural Fool to speak in riddles and give voice to a harsh wisdom from the depths, telling the king what his conscious mind refuses to hear.

Three centuries later, Freud tried to reconnect us with our Inner Fool. Our shadow, who still speaks to us in riddles, but only at night, in our dreams, or occasionally in our slips of the tongue, as though another voice were speaking our thoughts, revealing what we honestly meant, but have tried to repress from conscious awareness.

Is it too much to see Armin’s invention of a new kind of fool – who no longer flatters his master, but challenges him to accept the inadmissible – as a crucial milepost, not only in the evolving lineage of the theater, but in the cultural history of Western consciousness? Is this not a link in a long (and broken) chain, going back to the daimones of Greece, those spirit voices from within, upon whom an ancient Greek could rely as a guide, a pyschopomp, a god-like entity greater than your reasoning mind, an ally who gives you a deeper non-rational connection to your life? And whom Christianity has cast aside, as the voice of the devil. A demon.

Look closely at the figure of the Fool on the marotte. Does he not look devilish? Those pointy ears, that mischievous grin? The daimon, transformed. Become a Trickster, who plays games with your conscious mind, holding up a mirror, whispering truths in your ear that you must listen to, or suffer the fateful consequences.

As Jung said, “Until you make the unconscious conscious, it will direct your life and you will call it fate.”

And now where are we, a century after Freud and Jung? Whenever our mind grows turbulent, our thinking caps impaired, our bearings lost, what are we to do? Take a pill!

And if the problem persists, then pills become meds. And the voices within are silenced, considered only as signs of a foolish madness.

Leave a comment