This is a photo that appeared in a local paper in Delaware County, where I live. They’ve been holding the parade in the town of Andes for more than 40 years. And as the story goes on to say, the main event of this celebration was “a reenactment of the fatal shooting of Delaware County Under-sheriff Osman Steele, an event that was considered the catalyst for the “Anti-Rent” movement.”

Yes. A parade led by the Sheriff’s Office that celebrates the murder of a sheriff. And there’s more. The Anti-Rent War began in 1839, and resulted in the abolition of the unjust feudal system that had tied a quarter of million tenant farmers in upstate New York to vast tracts of land owned by a few wealthy “patroons.” But the fatal shooting took place at a farm in Andes in 1845, at the very end of the conflict. So how can it be, as the local paper blithely asserts, that the event was considered “the catalyst”?

You walk into the room with your pencil in your hand

You see somebody naked and you say, “Who is that man?”

You try so hard but you don’t understand

Just what you will say when you get home

Because something is happening here but you don’t know what it is

Do you, Mr. Jones?

As the lyric of Bob Dylan’s “Ballad of A Thin Man” puts it.

It’s a song about a straight guy who goes into… a gay bar? – with a pencil in his hand, like a reporter – and they all have “pencils” in their hands too. But what he’s doing and what they are doing are completely different. He’s an outsider. And they are insiders.

So step into my Time Machine and let me take you back to 1845 to the town of Andes. And go inside, into The Hunting Tavern. And there he is, Osman Steele, standing by the bar, downing his second brandy.

It’s August 7th. He’s on his way to Moses Earle’s farm, to auction off some of Mr. Earle’s cattle, to collect the two-years’ back rent he owes. Osman knows there will be trouble. But he isn’t afraid. He turns to the other customers – all “up-renters” on the side of law and order – and says, as legend has it: “Lead cannot penetrate Steele.”

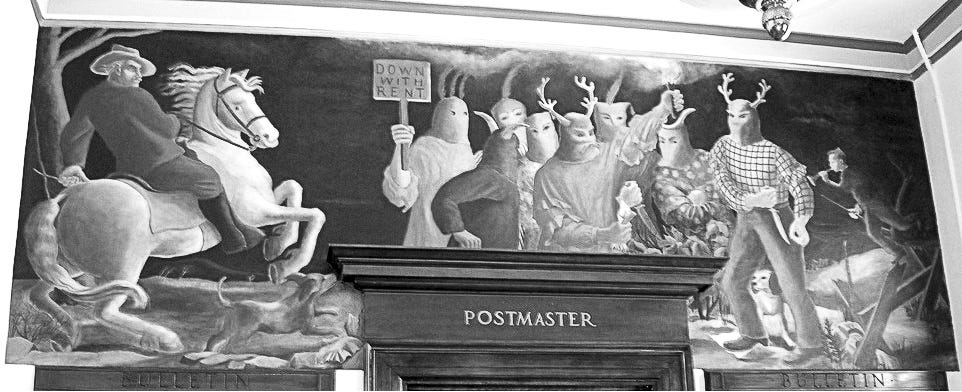

When he arrives at the farm, he is met by more than 200 armed masked men. They are all dressed up in weird and menacing costumes – as portrayed in the mural at the local post office in Delhi, the County seat.

They are doing their version of what they think the original inhabitants – who had their own lands appropriated by outsiders – looked like. Their outfits are woven together with strips of cotton, so they call themselves “Calico Indians.” They are mostly rowdy teenagers and young men in their early twenties. They are organized into “cells” with about a dozen individuals, each led by an older “Chief” – all with mock-Indian names like Red Jacket and Little Thunder. Jugs of whiskey are being passed down the line, to help them steady their own nerves.

And there’s the Under-sheriff approaching them on his white horse. And there is the little boy on the right, tooting the tin dinner horn they used to call the local farmers to arms. But all you see are a couple of men drawing knives. There are no guns in sight.

And if you ask the clerk behind the desk about it, he will hand you a postcard of the mural, and on the back it says: “The artist did not depict a specific event from the Down-Rent War, but sought to portray a typical meeting of the Calico Indians.” And what happened during these confrontations? If the Sheriff did not tear up his warrants, “he would be tarred and feathered.”

So there you have it. The deep sense of pride in the role these men played in leading the fight against a terrible system of injustice. And the inability to accept what really took place that day. The coroner’s report, based on sworn testimony given the next day leaves no doubt: he was shot three times, and the fatal bullet entered his lower back. He was killed only after turning away from the mob.

If you were at Moses Earle’s farm that day in 1845, you had to obey the Chief when he gave the order to fire. But at the same time, you knew you were taking a higher authority, the law of the land, into your own hands. After the Sheriff died, Earle Moses justified the murder on a still higher level, saying “The Almighty does not make mistakes.” The mob was only fulfilling the will of God.

Those aren’t contradictions. They constitute what the anthropologist Gregory Bateson calls a double bind, a term he coined in the 1950’s to denote situations in which you cannot choose between two (or more) conflicting messages – because they occur on different levels of abstraction.

They make you crazy. You are forever going back and forth between one level and another. The dilemma can’t be resolved. And soon you begin to make up things to alter the narrative so as to alleviate the pain.

Is it any wonder that the local paper has reversed the order of events, and made the murder of the Sheriff the “catalyst” for the entire Anti-Rent War? If that’s what it took to get rid of the old feudal order, surely that was worth the life of one man.

And since nobody knows whose bullet actually delivered the final blow, maybe it was just an accident and they were only aiming at his horse. You will hear that a lot from people who live in Andes. And the town’s own official website claims the Sheriff wasn’t even there – it was someone else – the “landowner” – who was murdered! Soon someone will be calling the mob “patriots.”

On and on it has gone. Year after year. It has become a ritual. At every Community Day, the trauma is reenacted. And the parade is led by the Sheriff’s Office. Like love and marriage, they go together like a horse and carriage.

But this isn’t just the story of Andes. It’s the story of America. Guns and freedom. Our national double bind.

Leave a comment