I gotta tell you about Edd. One of the nicest & most unusual guys I (or you) will ever meet, and it was only yesterday that I actually met him.

I had decided it was finally time to take care of my final business. On Earth. So I just walked into the MacArthur Funeral Home on Main Street — the only such facility in the town in upstate New York where I live — and plunked myself down on [in] one of those super-comfy armchairs they have in such establishments, next to the table with the bowl of mints and the Kleenex box.

And soon Edd appeared. Tall and lanky and dressed impeccably in a dark suit, and sporting one of those little comb mustaches that make you look older and more dignified than you really are. “What can I do for you, Sir.”

“I hope I’ve got it right: a ‘pre-funded, pre-need funeral agreement’.” Which I need.

“Yep, that’s it. You’ve come to the right place. Just step into my office and have a seat.”

And while he’s filling out the forms, I ask Ed (not knowing it’s actually “Edd” — a Polish nickname for… Eddiuz?) how long he’s been “working here.”

To which he replies, coolly, “Well, actually… I don’t. Work here.”

Huh? “But then why are you selling me a product from a company you don’t… actually work for? Are you some kind of scam-artist?”

“Nope, just filling in for Paul. The guy hasn’t had a day off in the last 5 years. It’s a supply & demand sort of situation.” And Death takes no holidays.

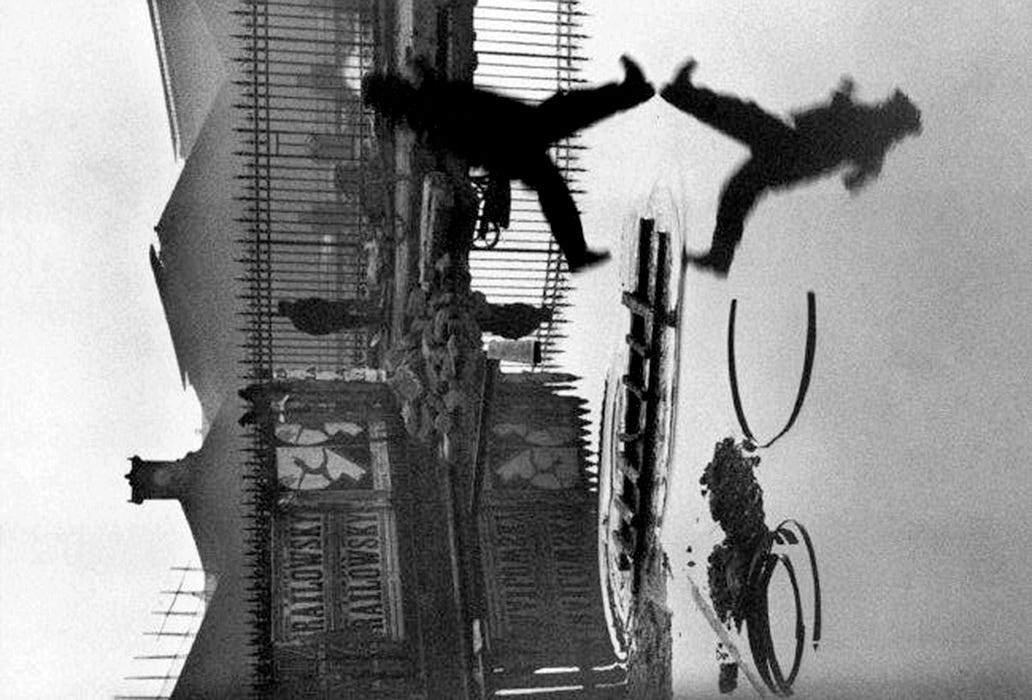

So here I must digress: Back about 1957, there was this TV show, a Western about a guy named “Paladin” (a medieval knight), played by this craggy-faced actor (Richard Boone), with a much better mustache than Edd’s.

Who had this calling card:

So that’s what Edd is — an itinerant funeral director. Have Hearse — Will Travel.

Slinging bodies instead of guns. Which he does, from his home in (even more rural) Madison County, about an hour north of here, to over a dozen funeral establishments, when the number of dead bodies (especially up here in flu season) exceeds the stamina of the resident director, and he calls Edd up and hires his services for a few days.

And just in case you’re wondering if he actually has a hearse, he does. But it isn’t brand-new, though Edd set up shop only a year ago. No, this hearse already had… 8000 miles on it. What? A used hearse with only 8000 miles on it?

Edd explained. The funeral director he bought it from lived in a small town. And the place where they kept all the stiffs was right next door, only a hundred yards away. So a round-trip was just 200 yards. Edd gave me a wink.

But still, do the math: 8000 x 1760 / 200 = 70,000 dead people, give or take a couple of thousand. That puts a completely different spin on it. As in spinning in… Or making your head spin… Which makes you wonder just how many of these folks actually died a natural death. Maybe John Gotti or Vinnie (The Chin) Gigante were neighbors? Who knows? And I’m not even going to ask Edd.

But one thing I’m betting I do know. That you’ve never thought about any of this in quite the way you are now.

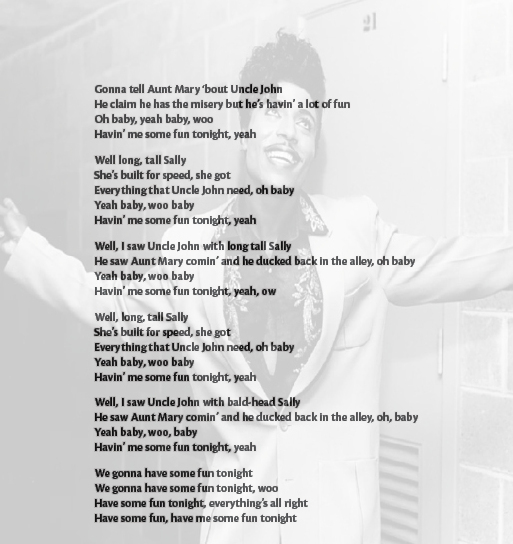

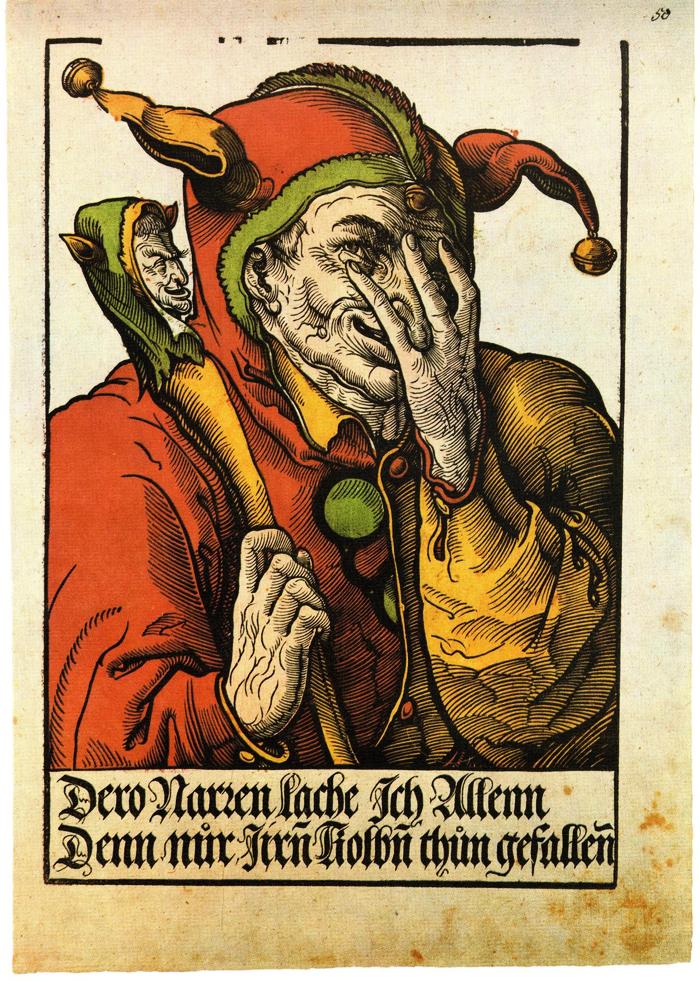

And while you’re at it, here’s a helpful tip I got from Edd. About burial urns. As I asked Edd about how I was going to get from the crematorium (I’m a Buddhist, so it goes without saying, though I just said it) to my final destination. Until my next stop – aka “incarnation” – perhaps as a dog (I’m quite ok with that) or a tree.

“A burial urn? Those can get pretty expensive. Some people pay more than a thousand bucks. Why do you need a burial urn if you’re having yourself cremated? If I may ask?”

And when I ask what the alternative was, Edd patiently explained that “I” (my “cremains,” as they call them in the biz) will come “pre-packaged.”

And he reaches behind and pulls out a sample. A shiny black plastic cube, about 9 or 10 inches per side. Which he opens and from which he pulls a clear Ziploc baggie. “Actually, you’ll be in here.”

And if I want, I can stay in there. As long as I like, or if I’d rather be scattered somewhere, by my loved ones, then all they’ll have to do is open the bag just a little, and start pouring. I just hope it’s a windy day.

I feel so much better now. No kidding. My mind is at rest, knowing about the rest of me. How about you?

And one last thing. I’ve read that everyone on Earth probably has a few atoms in their body that were once in Jesus. Or the Buddha. Or…